I don't usually enable visitor logs on my websites: I'm not chasing SEO and I have no need for in-depth analytics. However, I did notice that my site was using a shocking amount of bandwidth for how small it is. Most of my site is text, I try to use off-site hosts for large images and files as much as possible, and yet I'm still nearly hitting 3-figure megabytes of transfers per day. I can infer from the amount of engagement that I'm not getting the thousands of visitors per day that I'd need for this to be natural traffic, so I figured I must be getting victimized by the accursed AI scraper bots that are plaguing the open internet. Wanting to investigate, I turned on visitor logs on June 20 and I've been keeping an eye on my traffic since then. I've gleaned a few interesting insights.

Bots are scraping my site but they're not the main source of traffic

First of all, AI companies do have bots that identify themselves and respect robots.txt. I didn't have a robots.txt file before, but now I do. Whenever I see a new bot pop up, I add an entry for it to the list. They'll periodically scan robots.txt but make no additional requests.

However, this is just a smoke screen: scrapers are still visiting my site disguising themselves as normal browser traffic. I've heard that they'll mangle the user agent string, putting nonsense random version numbers in there, but even real, normal browser user agent strings are like gibberish to me, so I haven't made an attempt to distinguish them this way.

💡 Aside

Here's what my own user agent looks like when I visit the site from chrome on an android phone:

"Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; Android 10; K) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/136.0.0.0 Mobile Safari/537.36"

Ah of course, Mozilla's Chrome mobile Safari. You know, it's like Gecko!

The easiest way to identify these bots is by their behavior. When real people visit the site, I can see their tracks. They might start on the main page, click the link for the most recent blog post, read it, click the "blog" link at the top of the page, click a link to another post, etc. When it's a bot, they directly access pages deep in the site's structure with no referrer. Their navigation doesn't follow logically from one page to another. They visit pages without downloading the images on those pages, because they're instructed to just slurp up all the text. No real human is accessing my website by directly typing the URL in and navigating exclusively by copying and pasting links, and also has images disabled. They're bots. I can't prove they're all AI company scrapers, but Occam's razor, that's what they are.

This doesn't really accomplish anything but satisfy my curiosity. I can't do anything with this information. There's no portion of user agent string I can block without surely also affecting some number of real visitors. The IP addresses are all over the place. I figured this would be the case, otherwise people wouldn't need to use cloudflare and proof-of-work gatekeepers.

What I've learned is that I don't yet need to start looking into these mitigation techniques. I'm angry that my site is being scraped, and they shouldn't be allowed to do it, but my site is small enough that this doesn't represent a big chunk of my traffic. They're not repeatedly scraping the entire site, just random pages throughout the day. It's maybe a few MB of data, most of the transfer is coming from other sources.

Wikis are especially vulnerable to malicious bots

One truism about having a site on the open internet is that you're going to be hammered by bots looking for exploitable infrastructure. This has been true for decades, no matter how big or small your site is, you're going to get hundreds or thousands of requests a day for known exploitable scripts that crackers can use to either gain control of or inject malicious code into your website. The vast majority of these are for Wordpress plugins, because as they say, "Wordpress powers the web". For the love of god, don't use Wordpress. It's run by a megalomaniac and it's leakier than an Oceangate sub.

For a static website or one with any other CMS, this kind of probing isn't that big of a deal. They'll get 403 or 404 errors, the pages for which are probably only a few bytes. I guess if you're big enough you can still get DDOS'd through sheer number of requests, but I any site that big probably has enterprise-grade solutions.

It poses an interesting problem for a small personal wiki though, because when you try to visit a page that doesn't exist, you're redirected to a module that allows you to create that page. So if a bot probes https://mattbee.zone/wp-content/plugins/seoo/wsoyanz.php to see if it exists, my wiki thinks they want to create a page called wp-content/plugins/seoo/wsoyanz.php and loads the UI for doing so, which includes a PHP request the full layout HTML. This isn't a massive expense, each request like this is only about 5.5KB, but when you're hit with thousands of them, it can add up pretty quickly.

My first idea was to add rules to my .htaccess returning a 403 error to any request for a URL that contains "wordpress" or "wp-":

RewriteCond %{QUERY_STRING} ^.*wordpress.*$

RewriteRule ^ - [F]

RewriteCond %{QUERY_STRING} ^.*wp-.*$

RewriteRule ^ - [F]

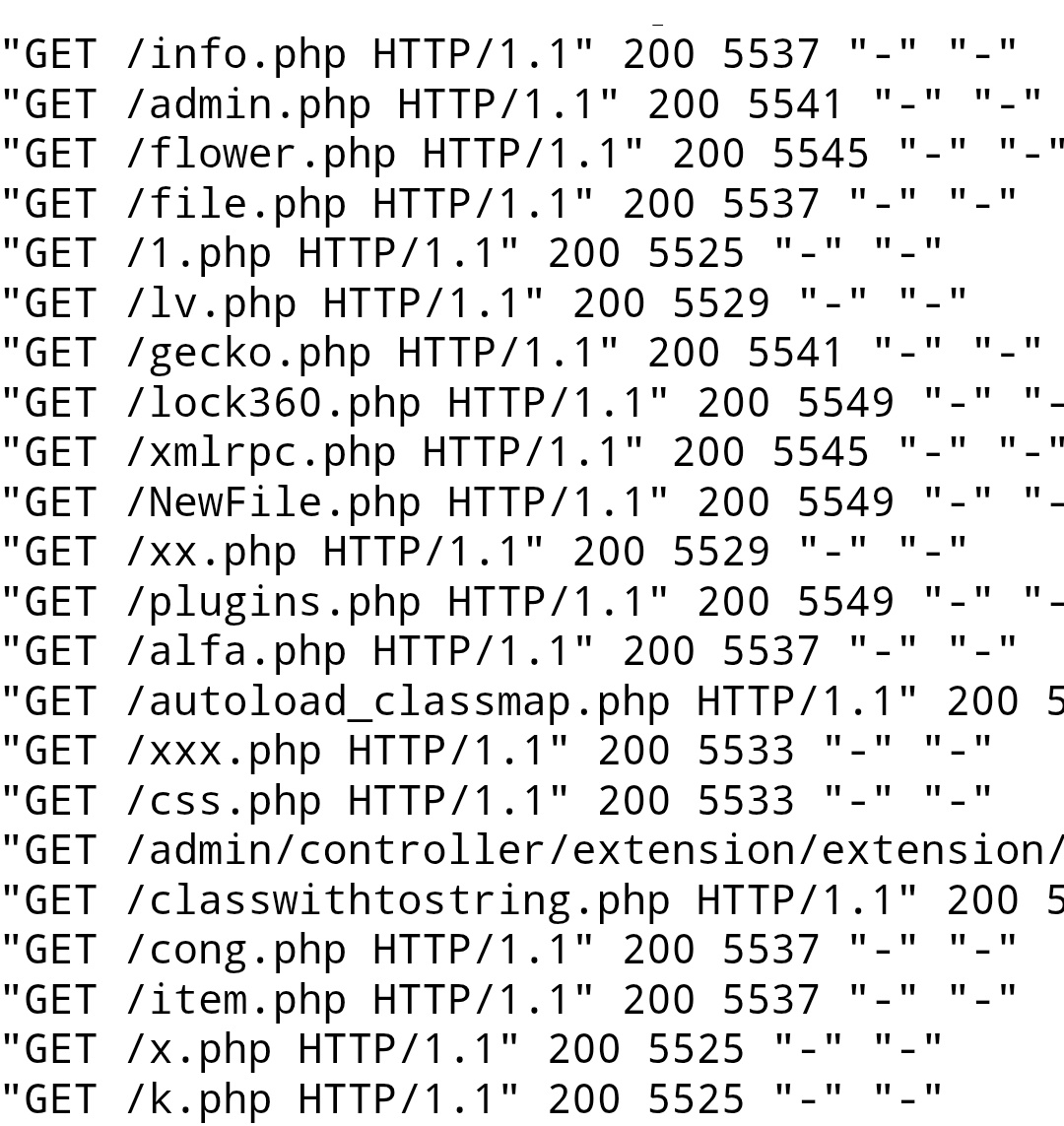

This was pretty effective, and reduced the data transfer from these requests by 99.95%, but they're not just looking for Wordpress installs. There are plenty of requests from bots looking for any and all scripts with a chance they might be able to get their oily little robot fingers in:

I thought about trying to craft a rule that blocks any URL ending in "PHP" except the ones I actually use, but finally I decided I'd try to disable this page creation feature entirely.

Calling mattbee.zone a "wiki" is sort of a misnomer, because if you ask people what defining feature makes a wiki a wiki, most of them would probably say something about collaboration. A wiki is a site that a lot of people can contribute to. "Personal wiki" usually means a database of specific knowledge or a note organization system (public or private) kept in software like notion or obsidian. I think most people wouldn't think of my site as a wiki, and the only reason I use kiki in wiki mode is because it allows me to edit my website from my website. That's it, that's the function I want from a content management system: I want to be able to make changes without needing to open an SFTP client or SSH into the server every time.

Which is good, because kiki lacks some of the features that would make it a wiki in a traditional sense. One could technically use it for collaboration, but it doesn't support multiple identities, you'd have to share the password with whoever you want to collaborate with. It doesn't have document versioning, so if someone makes an unwanted change there's no way to undo it. It doesn't support "red links", so if there's a page that doesn't exist yet but might in the future, there's no way to easily differentiate it. All of this is fine, none of it is stuff I personally need, but it does make "redirect any request for a non-existent page to the UI for creating a new page" more of a liability than a useful feature. I took a dive into the code to see if there's a way to disable it without disabling wiki mode entirely.

There is! And it's easy! Just change this line in library/page.php:

elseif ($action["command"] == "new" && function_exists("create"))

$page_source = create();

To this:

elseif ($action["command"] == "new" &&

function_exists("create"))

$page_source = die("404");

This will make any request for a page that doesn't exist, for example butts, error out with a message that says "404" instead of inviting you to create a new page called "butts". Which means all those thousands of requests from malicious bots will now return 3 bytes instead of ~2000. This is not technically correct, since the http code returned to the client is not actually 404, but I'm not too worried about it.

Most of your RSS readers are misbehaving

This is the the most surprising thing I learned, and the cause of most of my unaccounted-for traffic. I want to stress that I appreciate everyone who subscribes to the blog, no matter how you do so: I'm thrilled that so many people are interested enough to stay subscribed, and I don't blame any of you for this: it appears to be an industry-wide problem.

The problem is this: almost every RSS reader that interacts with my feed is downloading the entire feed every time it refreshes. The feed currently contains the entire contents of this blog, and is ~250K. That doesn't seem like a lot, and I didn't think it was too big, but I had assumed or had read somewhere that RSS clients check to see whether the feed has been updated first before downloading it. This seems like the obvious, common-sense thing to do, but almost none of the ones I've seen in my logs do it.

There are two ways that I know of to accomplish this: the first and most straightforward is to use the http HEAD command to get the metadata and check that it's different before you actually GET it. You can check this yourself with curl:

curl --head https://mattbee.zone/rss.xml

HTTP/2 200

date: Thu, 26 Jun 2025 13:51:12 GMT

server: Apache

last-modified: Thu, 26 Jun 2025 13:32:00 GMT

etag: "4074f-638799614f02e"

accept-ranges: bytes

content-length: 264015

content-type: application/xml

via: e9s

Note that the "last-modified" field doesn't necessarily correspond to when the blog was updated. At time of writing, the last blog post was June 24, but the rss.xml was last modified today. That's because kiki re-genererates the feed every time the site loads, to make sure it always includes every post that's been tagged blog.

So if I were designing an RSS reader, I would compare the content-length field. Because the file is still 264015 bytes, you know it hasn't changed since the last time you fetched it, so you don't need to download it again.

The other way is to use a GET request with two specific headers, and if the file hasn't changed since the last request, it'll return a 304 response instead of downloading it. Thanks to Louis Vallat for pointing this out when I was complaining on Fedi:

Looks like Commafeed doesn't do a HEAD request but a GET one, but as it sets the

If-None-Matchand theIf-Modified-Sinceheaders, the server is able to reply with a304 - Not Modifiedand an empty body.

I haven't seen commafeed in my logs, but there are two clients that use the 304 method. They're Feedly and RSS Guard.1 The rest of them, to a T, download the entire XML file every time they update the feed, however often you have them set to do so. If your client refreshes feeds every 10 minutes, that's currently 36MB of data per day just to confirm that the feed hasn't updated, and as I continue blogging, the number is going to keep growing. Clients I've seen that exhibit this behavior are:

CapyReader, Feedbin, feeeed, flym, FreshRSS, inoreader, miniflux, NetNewsWire, NextcloudNews, rss2email, Vienna, and YarrEdit Jun 28 2025: None of this is accurate! The problem is the way I was generating the feed! Kiki constantly re-generates the xml file whether the blog's been updated or not, just in case. This is cheap enough on the server end not to be an issue, but RSS readers look at the last-modified or etag value to determine if the file has changed, not the file size. I changed how RSS generation works and nearly all of them are getting 304 codes and using no bandwidth. I apologize for impugning the aforementioned RSS clients.

I'm also seeing a lot of requests with a generic browser user agent, which may be browser-based services like vore.website.

Again, no beef with anyone who uses any of these: I mostly read feeds with flym and vore.website myself, and I always assumed they were respecting bandwidth. I'm going to look for alternatives, and in the meantime, I'm probably gonna clean up my feed to make it only include the 5 or 10 most recent entries. With kiki the only way to do this is to go back and manually replace the "blog" tag with some other tag, which will suck, but I'm glad I noticed this now and not some point in the future when I have 500 posts to fix. Maybe I can try to figure out a way to automate it. Programming! It's the future! $$hacker$$

Fake edit

I was pretty much done with this post, but I wanted to learn more about 304 codes and try to figure out how this works, when I found the following:

‹etag_value›

Entity tags uniquely representing the requested resources. They are a string of ASCII characters placed between double quotes (Like "675af34563dc-tr34") [mdn web docs]

If I do a HEAD request, refresh my page, and do another one, the etag value is different. I think the way kiki generates the RSS feed might be the culprit. If the majority of RSS clients are looking for the etag value, it's natural that they would download the file every time. As far as they know, a different etag must mean the feed has been updated. I don't necessarily think this is a safe assumption to make, but if RSS feeds work this way 99% of the time, I guess I can't really blame them.

I'm also not sure what differentiates RSS Guard, maybe there's a GET header that specifically compares by file size, but whatever the case, it's clearly an outlier. I think my next move will be to try to modify kiki so it only generates the RSS feed when I give it a specific command rather than every time index.php is accessed, and see how that affects the client behavior. I'll let you know how it works out $$hacker$$